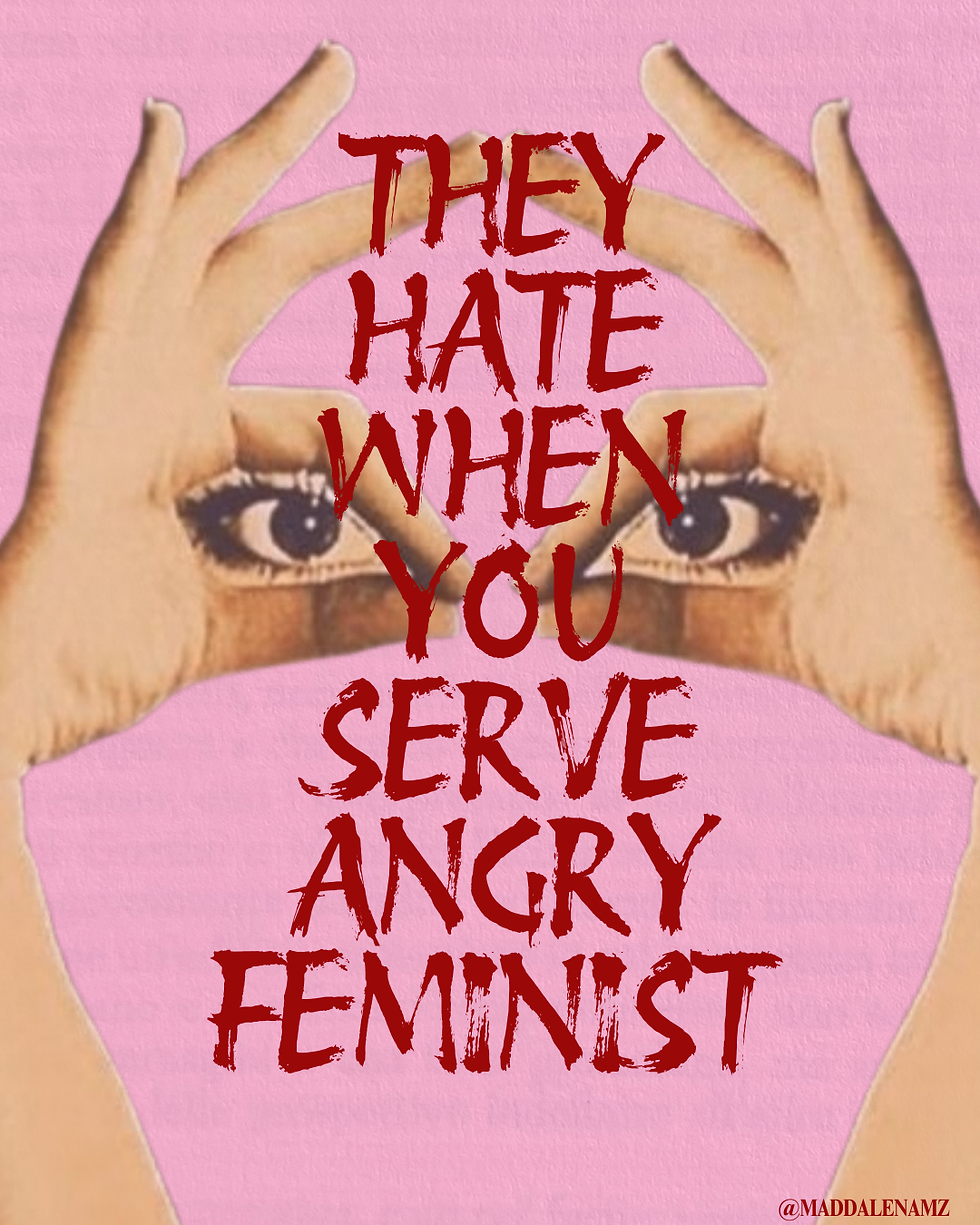

They Hate When You Serve Angry Feminist

- Maddalena Mizzoni

- Apr 23, 2025

- 3 min read

Updated: Oct 24, 2025

People love to put you in a box.

Mine was obvious from early on. When I was eight, I learned the word “feminism” and immediately decided it explained everything. It made sense of things that had been bothering me, things I didn’t know how to talk about. From that point on, it became the framework for how I saw the world. Not just an interest, not even just a belief, more like a lens I couldn’t take off. I was feminist, and I was angry, and that combination seemed to make sense to people. It gave them a way to understand me.

By the time I was a teenager, the role had settled around me. I was the one who got into fights about politics. The one who made boys uncomfortable and adults defensive. I argued constantly. Sometimes I enjoyed it. I liked knowing more than other people, and I liked knowing I was right. But it also meant that when people looked at me, they stopped seeing anything else. It was like they’d decided: this is what she is. She’s intense. She’s political. She’ll correct you if you say something off.

And I accepted it, mostly because I didn’t know what else to do. I had built a whole way of being around that idea. I read bell hooks and Audre Lorde. I memorized quotes and used them in arguments. I believed deeply in everything I was saying. Still do. But there was also a certain pressure underneath it: the feeling that the world was broken and I had some kind of duty to fix it. That if I stopped being angry, even for a minute, I was letting something slip through the cracks.

Although this pressure sounds admirable in theory, in reality, it turns you into someone who never lets themselves rest. I didn’t feel like I was allowed to be tired, or vague, or ordinary. If I wasn’t always certain, always fighting, I felt like I was failing at something.

Eventually I started noticing how much I was leaving out. The fact that I liked silence. That I wanted to work in the arts, not in politics. That I didn’t always have a good response. That I could feel strongly about something without needing to argue about it. These weren’t things I ever really admitted out loud. They didn’t match the version of me I’d spent years performing.

It made me wonder if I was still doing it right. If I was still a good feminist, or just someone who used to be one. And that question, that suspicion that I was somehow failing just because I wanted to be more than one thing, that was patriarchy too. The idea that a woman can only be taken seriously if she is entirely, visibly consumed by the fight. The idea that softness is weakness. That joy is distraction. That complexity is betrayal.

My fear itself was part of the problem. It wasn’t freedom. It was YET another kind of performance, just a different set of rules. I hadn’t really let go of the box. I’d just decorated it differently.

I still believe in the things I believed in at 14. I still think the world is mostly unfair and sometimes violent in ways we’ve normalized. I still get angry (a lot). But it’s not the whole story anymore.

Now, I also let myself want smaller things. To spend time alone. To take photographs. To feel quiet and not explain it. That doesn’t mean I’ve stopped caring. It just means I no longer think self-erasure is a form of political commitment.

I used to think I had to be everything all at once: correct, consistent, invincible. But if there’s one thing I know now is that there is no point in being free if you can’t also be yourself.

Comments